Balancing Authenticity and Functionality: An Introspection of Re-engraved Scores in Music Theory and Analysis Textbooks

My thoughts have been preoccupied with an important question for a significant period, and I now find myself with ample time to carefully contemplate it and commit it to writing.

It has come to my attention that there is a perspective advocating for the use of an ‘original sheet music’—or more precisely, scores initially published by their respective publishers—in music theory textbooks and practice workbooks, particularly those that pose examination-style questions or contain entrance mock tests. Proponents of this approach argue that it highlights the authenticity of musical notations and showcases the artistry of music score editing, rather than depending on reproductions that have been re-edited by the textbook publisher.

This assumption and statement (purportedly allowing readers to view the original version of the score) are both somewhat perplexing.

Firstly, we will examine the musical examples employed in most classical music theory analyses throughout this article. We will also explore the manner in which scores collected in music history are presented. For illustrative purposes, I shall reference three music history textbooks that are widely recognised in Europe, the United States, and other countries (the instances of music theory textbooks will be discussed later). Grout, Stolba, and Bonds have published music history books through three esteemed publishers, namely W. W. Norton and Company, McGraw Hill, and Pearson. Upon inspection, it is apparent that these examples have invariably been re-notated, or more precisely, re-engraved. when the editorial departments of these publishing houses processed the musical score examples (or some basic music analytical examples) in their respective publications.

This observation raises a pertinent question: under the aforementioned concept, would the use of the original publisher’s score not better exemplify authenticity? Furthermore, should music history books not adhere more closely to this principle, thus enabling readers to examine the intricate details of original score publications?

In response to the question presented above, I aim to provide a clear and concise elucidation whilst also explaining my own introspection to highlight why publications opt to re-edit all musical examples rather than incorporate the original sheet music:

- Given that our primary focus is not on ‘original research,’ ‘manuscript study’ or even ‘comparison of score versions,’ the insistence on utilising the original published score proves to be inconsequential.

- It is entirely within the realm of standard practice for the editorial department to re-engrave specific musical passages, as the accurate selection and extraction of particular segments is paramount to their purpose.

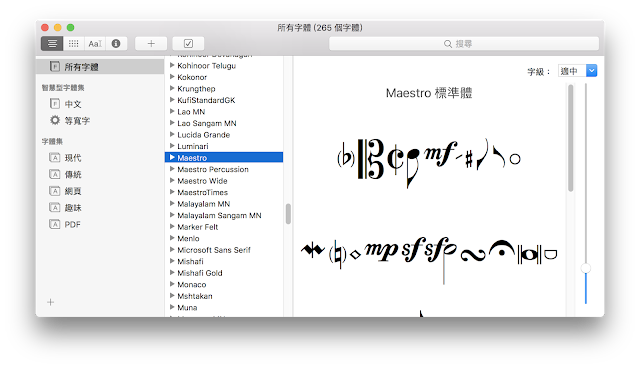

- Upon examination, it will become evident that scores have been invariably re-engraved, even when these textbooks have published their own music example collections (e.g. Grout). The use of the original publisher’s score may only be feasible in cases pertaining to twentieth-century works or those employing specialised notations.

- With regard to emphasising the authenticity of the music score display, it should be noted that manuscripts have been published by numerous entities. All scores have been beautifully edited, albeit in different ways, which raises the question: what is the standard of choice? (Does the entire textbook use the music scores first published by the original publisher? It is doubtful that textbooks published by critics universally employ first-edition music scores.)

留言

張貼留言